I had the chance to visit Nairobi, Kenya, this week on a work trip, so I thought I would skip the usual tourist traps and see what I could learn about beekeeping in Kenya. It turns out there was a lot to learn!

For one thing, my driver, Eric, was a beekeeper. He is a member of the Kamba people from eastern Kenya -- a group famous for their beekeeping skills. He keeps 20 hives at his shamba (farm or garden) about 240 km outside Nairobi. In old-school Kenyan fashion, he keeps his bees in hollow logs and scrapes the comb out (he mimicked reaching his arm inside the log) to extract the honey.

While I didn't get to see Eric's apiary, I did get him to drive me to the local beekeeping supply store.

The Hive Group Ltd. runs pollination services all over the country and, as a result, sells honey from all over the country. It also has multiple retail outlets in major cities.

Among my souvenirs from Kenya is this eight-way bee escape -- a tool I had never seen before and immediately wanted to try when I do my first honey extraction in June. Last year, I fought the bees for their honey. This year, we'll outsmart them. While I had never seen such a device, they're apparently popular elsewhere in former British colonies, as t

his video from New Zealand can attest.

Honey from Kitui County, which is the Kamba heartland, is supposed to be some of the best honey. But it all looked amazing, to be completely honest. Like all beekeepers, the people at The Hive Group were happy to chat about bees (nyuki in Swahili).

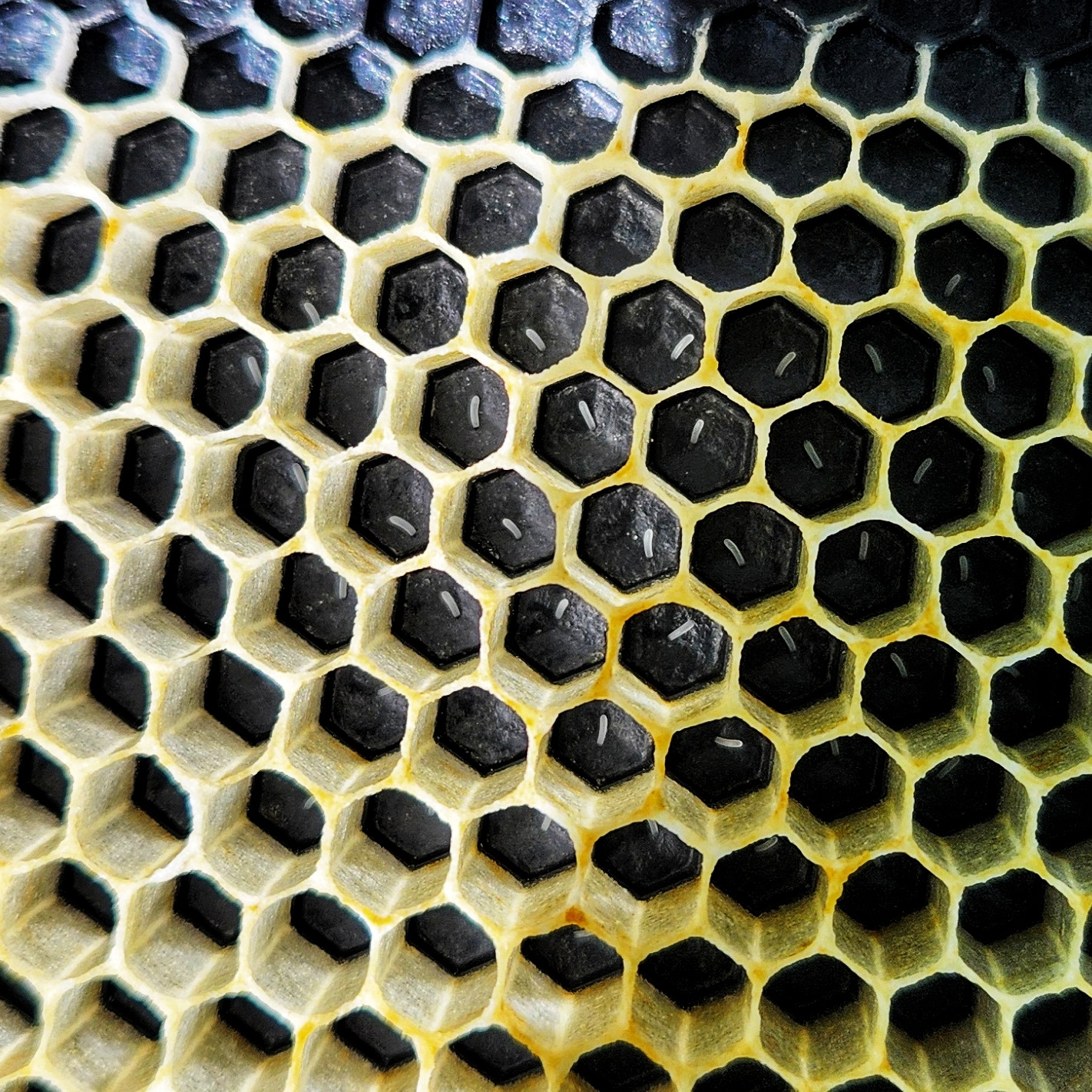

Project Manager Richard Kyalo Philip showed Eric and me one of the modern versions of a traditional log hive. This one works like a horizontal hive with round frames instead of rectangular ones.

The curved lid folds back to give you access to the frames, so no more shoving your arm up into a log full of bees and honey comb. (Eric was intrigues.) The set costs about $100.

They also use top-bar hives, which appear to be popular in Kenya, as well as the old Western standard Langstroth hives. The shop was busy with people coming in to buy equipment and get into the business.

A

story from May 19 in Kenya's Daily Nation newspaper reports that Kenya's beekeepers are struggling with hive losses and falling far short of the national demand for honey even as the number of beekeepers is growing. Like other country's they may have to start importing honey from elsewhere.

The Hive Group has been around about 10 years and is so connected to Kenya's beekeeping scene that they are Number 001 among the members of the Kenyan Beekeeping Association (which is headquartered just around the corner).

If anybody in Nairobi is looking to expand their apiary by catching/relocating a swarm, I found one for them. On my first day in town, I took a walk through Uhuru Park where I noticed a stream of bees beelining for a hole in a metal light pole.